The LARGEST theropod dinosaur known to science…

…and how certain can we be?

One of the highest points of contention online regarding dinosaurs, is one question: what was the largest meat-eating dinosaur? Whole threads, websites, and individuals are dedicated to answering this question, often leading to intense arguments, or worse. Death threats are thrown, and people are impersonated, all because someone said their favourite dinosaur was smaller than another.

I think it’s important to clarify a few things before presenting a more scientific approach to answering this, oh-so-contentious (for no reason) question.

Number 1, and probably most importantly: we will never know the largest individual of a certain species. In all likelihood, the sizes of individuals of species would be around average sized, statistically speaking -this is because “average” animals are more likely to fossilise as they are more common, with statistical outliers (such as exceptionally large individuals) being very rare in life, and so even less likely to fossilise.

Number 2 (perhaps equally important): some of the largest theropods we know are not well preserved. I’ll go into this in more detail later, but essentially speaking, many of the likely largest species we are aware of are not complete, or worse, taxonomically complicated. Estimating the sizes of these particular genera can be much more difficult.

Number 3: Finally, estimates vary from author to author, especially in the case of taxa that aren’t as complete. Even minor details, such as rib articulation, the number of bones, or relatives chosen to fill in gaps, can result in very different sizes – particularly in large animals.

Accordingly, the sizes mentioned below in my blog may vary slightly between different authors. This does NOT mean that one estimate is “more accurate” or “official” compared to the others (these are words I see thrown about very often in the paleo community). As long as the reconstructions follow the known material in the best way possible on what information is available, each is likely just as accurate as the other. In the case of less well-known theropods, this can still result in wildly different estimates. The estimates I will be presenting below are my own, based on the largest individuals WE KNOW OF, and reconstructed myself. It’s important to recognise other authors may find slightly different results based on different methods, some of these reconstructions being no less valid than my own. Of course, I will be providing reasoning for each of these measurements, including my methods, which you are welcome to replicate and fact-check against your reconstructions.

Finally, if your favourite dinosaur is not represented here, it is important not to get angry or heated. After all, it does not matter which animal is larger, and which would “beat the other in a fight”. There is no scientific answer to any of these questions other than random speculation, especially as the majority of these animals lived in vastly different regions and times. Overall, the size of a few long-dead animals should not, to anyone of a right mind, result in a heated argument or worse. This includes name-calling, insulting, libel, belittling, dismissing results based on little but personal opinion, death threats, or impersonation (all of which have occurred as a result of dinosaur sizes – believe me, I know.)

Right, now that we’ve established that overall, this question has no definitive answer and really shouldn’t matter that much, let’s get into my estimates for some of the largest theropod dinosaurs.

All length estimates are along the centra of the vertebrae – as neural spines, and the silhouette of the body, can influence the length of an animal dramatically, a centra measurement is best for comparison’s sake. A straight line measurement is perhaps even more variable, as the pose of the vertebrae influences this dramatically (I’ve seen a lot of grid-based size charts simply scaling a silhouette to a certain size, which often vastly oversizes an animal.) The weight of each animal is determined via volumetric and/or GDI analyses, which are specific ways to determine the weight of an animal using these models. Bone density is in kg per dm^3, obtained from separate sources for different taxa.

TYRANNOSAURUS REX

The most famous of the large theropods - ask anyone on the street not interested in dinosaurs, and they will have heard of the mighty T. rex. Luckily for palaeontologists, the infamous tyrant lizard king is known from multiple well-preserved skeletons, enabling a very complete picture of even the largest individuals to be reconstructed. But does this apex predator hold the crown for the largest theropod dinosaur? One of the largest specimens, nicknamed “Sue”, is over 90% complete, which enables for pretty precise size estimation. Sue preserves much of the vertebral column, including the entire (albeit crushed) skull, allowing us to measure the entire length of this animal along the centra, being around 12.39 metres in length (based on the skeletal by RandomDinos).

Tyrannosaurus rex, “Scotty” specimen, possibly the largest Tyrannosaurus specimen.

Other specimens of Tyrannosaurus reach similarly extreme sizes: "Scotty”, a tyrannosaur specimen unearthed in Canada, is less well known than Sue, being around 70% complete – though this is still a substantial amount, which coupled with how complete Tyrannosaurus is, enables us to determine the size of this specimen. The majority of the elements recovered from Scotty are larger than that of Sue’s: for example, Scotty’s femur is very slightly larger than Sue’s 133 cm long femur with a circumference of 59 cm, compared to Sue’s 132 cm length and 58 cm circumference. You can probably tell that Although slightly larger, the difference between the two individuals is minimal. My estimate of Scotty puts the animal at around 12.37 metres long (slightly shorter than Sue’s) but with a larger weight of 10.4 tonnes with a bone density of 0.97, which is supported by a more robust femur adapted for carrying a heavier weight.

The large barrel-shaped torso, thick skull and robust limbs of Tyrannosaurus compared to other large theropods, places this heavyweight as a strong contender for the largest theropod (in weight, not in length). Previously, my model of Tyrannosaurus gave the tyrant its crown as top dog - but does this still hold up? I explore some of the other contenders below.

GIGANOTOSAURUS CAROLINII

Carolini’s Giant southern lizard hails from the Late Cretaceous of Argentina, though many millions of years before Tyrannosaurus rex lived. This huge brute is often considered one of, if not the largest, carcharodontosaurids. Since its discovery, many have considered Giganotosaurus the largest of the theropod dinosaurs – being known from two equally large specimens: the holotype, which is around 70% complete, and a referred dentary specimen which is larger in size. Unfortunately for us, much of the Giganotosaurus holotype remains undescribed: the measurements of the vertebrae, pectoral girdle, and other elements of the body are yet to be described and figured, meaning much of the information researchers can currently glean from this animal, is through the limited data that is available. Since its discovery, measurements of certain elements have been described which allow us to compare with other theropods and related genera – and we can tell it is big. Using what photos and measurements we have detailing the proportions of the animal, we can create a reasonably accurate model of what this animal looked like in life, as in my reconstruction (how I went about making my Giganotosaurus is explained in one of my old blogs here). My model of Giganotosaurus’ holotype, presents an animal around ~12.7 metres in length, and around ~8.8 tonnes in weight. Already, Giganotosaurus is longer than the largest Tyrannosaurus, but not as heavy here.

Giganotosaurus carolinii, referred dentary specimen MUCPv-95.

As mentioned previously, the referred specimen of Giganotosaurus, a dentary, is larger than that of the holotype. Exactly how large the specimen was in comparison was originally unclear: the only measurement included for both specimens was the depth of the dentary, with the larger jaw being roughly 2.2% larger. Dentary height can often be variable amongst members of the same species, but alas this was all I had - so previous estimates using my reconstruction placed MUCPv-95 (the dentary specimen) at roughly 13 metres long and 9.5 tonnes. However, recently I was in contact with Omar Lagarda González (aka Darknix), who was contacted with measurements of the jaw of the referred specimen. This allows us to use a far more reliable estimate, being the length of the dentary with respect to the number of dental alveoli, which varies less among members of the same species: this gives us a size difference of around 6.6% between the two specimens, resulting in a humongous size of ~13.5 metres and 10.4 tonnes in weight with a bone density of 0.97.

If this estimate proves more correct, Giganotosaurus ties in with Tyrannosaurus as the largest theropod in weight, being much greater in length - in contrast to my previous estimates. Although this size has a higher margin of error, due to the fragmentary nature of the dentary specimen, and the lack of description of the holotype, we can comfortably say that Giganotosaurus at least rivals Tyrannosaurus in size. On top of this, Giganotosaurus is only known from two specimens, both likely over 12 metres in length; if Tyrannosaurus is anything to go by, a genus with a large variation in size amongst adult individuals, it may prove with additional discoveries that Giganotosaurus was capable of attaining even larger sizes than the specimens we currently possess (some footprints from the Kokorkom desert of the candeleros formation may represent such enormous individuals…).

SPINOSAURUS AEGYPTIACUS

The famous Spine lizard from Northern Africa is one of the most enigmatic of the theropods, with a tall sail and long, crocodile-like snout. Unfortunately for us, the original holotype specimen was destroyed in an Allied bombing raid on Germany during World War II. Since then, multiple new spinosaur specimens have been discovered in the region, including the proposed neotype specimen - preserving a decent chunk of the vertebral column and displaying weirdly short legs. Although we can’t be sure if this specimen is the same species as the original holotype (which no longer exists), it’s the best we currently have to reconstruct this predator. My reconstruction of the neotype specimen presents a length of 10.56 metres along the centra (a measurement along the curves of the silhouette would obviously lead to a much larger estimate.) With this length, the animal would be far from rivalling the largest theropods; however, other large spinosaur specimens exist - although their assignation to Spinosaurus is perhaps even more questionable. One enormous rostrum, MSNM V4047 (sometimes referred to as the “Milan specimen) was an enormous spinosaur - however, neither the holotype or the neotype preserve this section of the rostrum. In order to scale this specimen, you kind of have to fit the jaw with that of the bottom jaw (preserved in the holotype). This does produce a huge estimate: using my reconstruction, you get an animal 14.2 metres along the centra. A similarly sized specimen, a dentary (NHMUK VP 16421), results in a similar size - this may be more accurately scaleable as the holotype preserves a dentary.

“Spinosaurus”(?) specimen MSNM V4047, size estimated from my own model. The exact proportions of this animal are still unclear, and it remains uncertain whether this specimen actually represents Spinosaurus.

The weight of the animal is even more tricky to determine, as the anatomy of spinosaurines such as Spinosaurus is currently poorly understood, and thus dependent on a number of variables; for instance, the angle of the ribs compared to the body can influence the weight of the body cavity, the amount of muscle used in the reconstruction (this applies to the other genera too), and the placement of the scapula - which may be further back from the typical placement around the first dorsal in other theropods due to the cervicalisation of the anterior dorsals. Using a modified version of the brilliant model from Sereno et al. 2022 (made by Dan Vidal), a body weight of ~7.8 tonnes is attained when edited slightly to the proportions of my skeletal, using a bone density of 1.05. Thus, my reconstruction of Spinosaurus presents the longest theropod, though not the heaviest by a few tonnes - if using the lighter bone density presented in Sereno et al. 2022, this results in an even lighter mass.

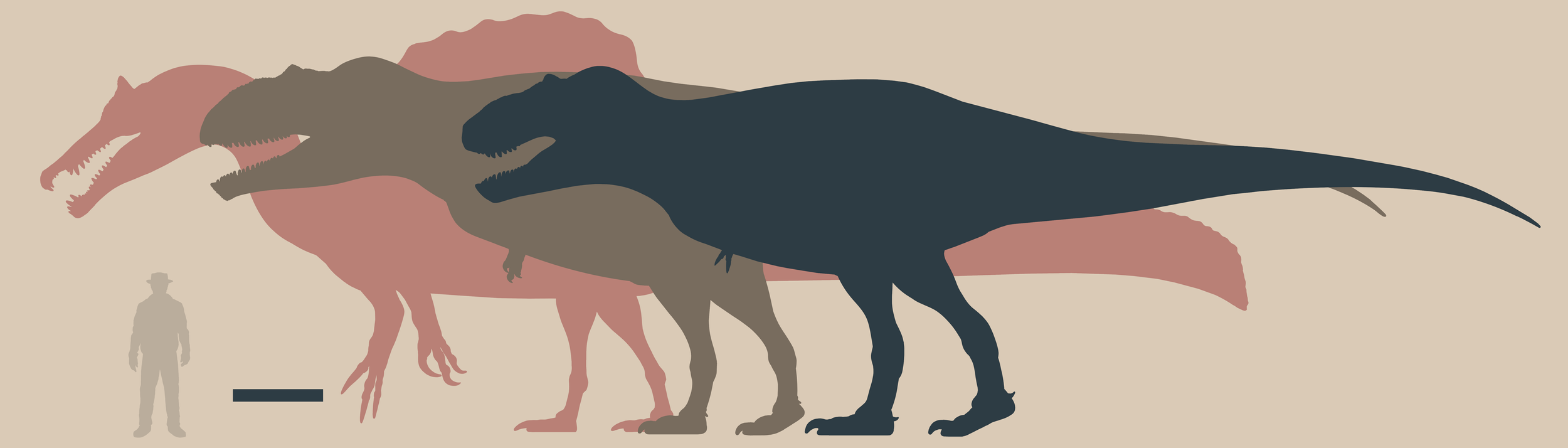

The “big three” theropod dinosaurs, from left to right: “Spinosaurus”, Giganotosaurus, and Tyrannosaurus. All represent largest specimens currently known to science.

Other taxa -

SAUROPHAGANAX MAXIMUS

A year ago today, I never would have considered this theropod to even be a candidate for largest theropod - the remains were just too scrappy, and very little of the material had actually been described. This has all changed very recently, however, I cannot currently produce a reconstruction of this animal, I will merely comment on some of the enormous dimensions of this animal. DJ Sandy (aka 7 shots), who is soon to be looking at the material of Saurophaganax, got in contact with OMNH, which provided him with some photos of Saurophaganax fossils, many of which are enormous.

Saurophaganax is known from 3 bonebeds from Kenton, Oklahoma, preserving around 9 individuals of this giant allosaur. One possible individual preserves some truly enormous material: an atlas, over 20 cm tall (much taller than Tyrannotitan’s, but of a similar width), a dorsal with a centrum 16.5 cm long (for reference, Giganotosaurus’ posterior dorsal is around 15-16 cm long), a humerus 50 cm long (Suchomimus’ humerus is 56 cm long), and a tibia estimated around 110 cm long (larger than Giganotosaurus’). These are some truly enormous proportions; however, without the rest of the material described, it’s much harder to compare the size of this predator with the previous big three at the moment. Once this material is described (hopefully soon) this may change.

CARCHARODONTOSAURUS SAHARICUS

The original shark-toothed lizard remains in a similar situation to Spinosaurus, being that the original syntype specimens have been destroyed. The holotype, however, did not preserve that much material, being only fragments of the body and skull. A neotype specimen, UCRC PV12, has been erected detailing well-preserved, large cranial material - though separate researchers question whether the lost syntypes and neotype actually represent the same genus, or if they are even related. As of the moment, it’s only possible to scale the neotype against the material of related genera, such as Tyrannotitan, which results in an animal roughly 12.3 metres long.

New material of a carcharodontosaur has recently been unearthed from similar strata to the neotype specimen. It’s possible that in a short amount of time, we will be able to reconstruct Carcharodontosaurus and further determine the relationships between these specimens. Until then, it’s difficult to estimate the size of this genus.

TL;DR

It should be clear now that estimating precisely the size of large theropods is very challenging - multiple variables, such as bone density, and several differences in reconstruction techniques, can produce wildly different results.

My reconstructions use the same techniques to maximise accuracy and show proportionality amongst the theropods I model. I must stress, that for all of these genera, a precise estimate for the length and weight of this animal will NEVER be found. This is the nature of the fossil record.

Thus, the takeaway here should be: do not get aggressive over the sizes of long-dead animals, they are bound to change with time, and the estimates above are only representative of current scientific understanding with my own reconstructions. Rise above your urge to get angry when someone provides a size estimate 1 decimal point smaller/larger than what your idea of an animal’s size is, and accept that after all, most of these numbers will change with time as more information and will never become conclusive.

Special thanks to, as ever:

DJ Sandy (aka 7 shots)

Omar Lagarda González (aka Darknix)

Henrique Paes (RandomDinos)

Small_midget

4LPH48

PaleoJoe

derpy.stego