Foot posture and gait in bipedal dinosaurs

EDITED: 02/04/23, 22:27 BST

Footprints and trackways are luckily pretty extensive for many theropods, providing a window in to the past detailing the way these large bipeds walked.

Recently, I was brought to the attention of a certain Spinosaurus paper (Sereno et al. 2022) which presents a wonderful skeletal model of Spinosaurus by Dan Vidal. All obvious Spinosaurus oddities aside, the skeleton displayed an interesting posture for the feet, pigeon toed pointing inward. Vidal explains that this posture is based on large theropod and ornithopod tracks from La Rioja, Spain, where the feet are pointed inwards – this got me thinking, was this a one off occurrence, due to the substrate where these prints fossilised? Or was this posture more widespread?

I recently did a deep dive in to theropod trackways, trying to find as many examples as possible to try and answer this question. Theropod trackways are known from across the world, and in a variety of different environments which provides a large sample size – I’ll post a link detailing all the different theropod tracks I looked at the bottom of this blog. Overwhelmingly, theropod tracks, particularly those of short gaits, seemed to be similar to those preserved in La Rioja. The toes pointed inward, with digit 4 pointing roughly parallel to the midline of the body (aka, the direction which the animal was travelling.) The footprints of this gait are usually positioned wide apart (though not extremely so). The figure below details this short, “pigeon toed gait below.”

“Short gait” biped walk, based on Ardley quarry tracks, detailing the inward pointing theropod feet.

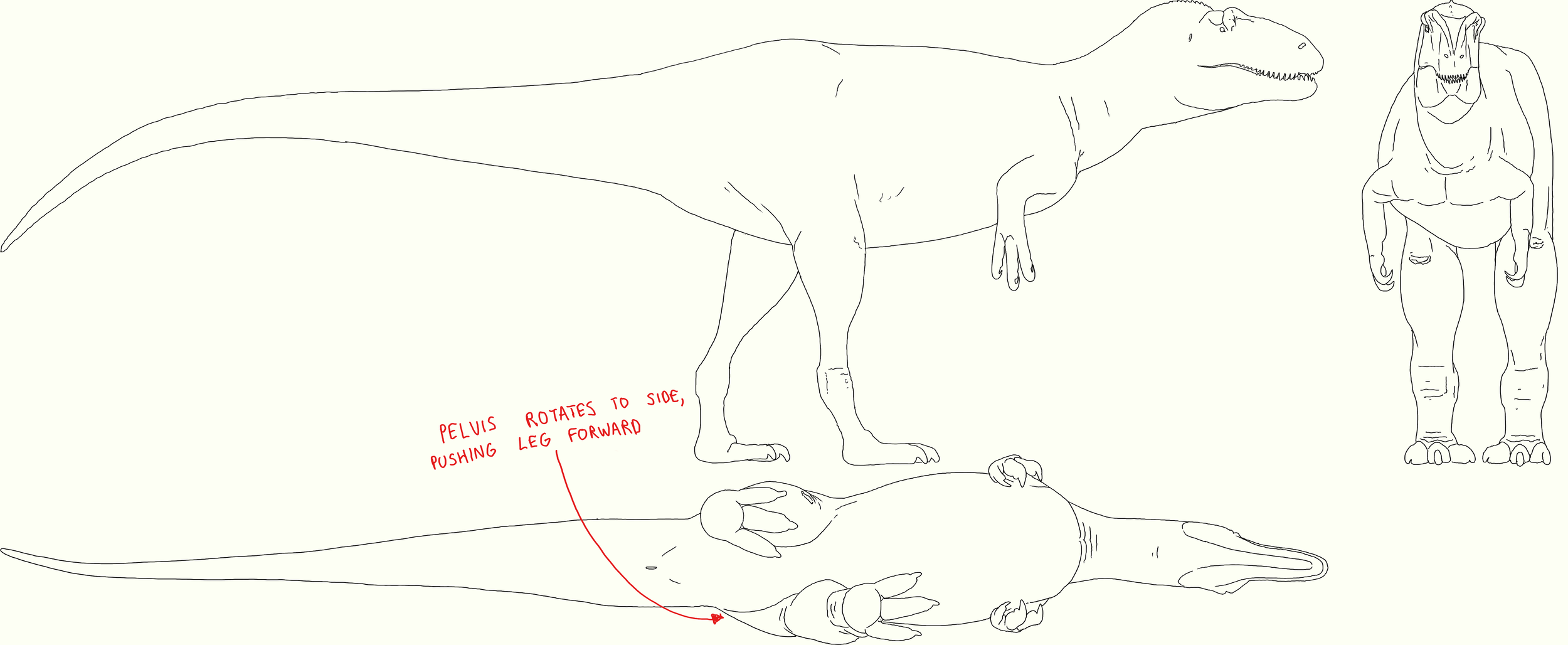

The metatarsals were probably unable to twist very much from the astragalus above. This leads to two possible ways that theropods moved to produce tracks such as those at Ardley Quarry: either by pointing their femur inward, or more likely, by rotating their hip from side to side. The back of the hip would rotate forward, in the direction of the leading leg, causing the torso in front to curve slightly and create space for the leg to move forward. This provides stability and involves the body moving in a fluid manner. The story is a little different when the animal switches to a longer stride, however:

The long gait details a faster moving animal, either running or in a long stride. It’s not sure what type of theropod made these tracks: either a Megalosaur like Megalosaurus, or an Allosaur like Metricanthosaurus – but we do know it was the same animal that was displaying the short gait earlier. Regardless, this animal was moving much faster. The tracks here do not point inwards; instead, the toes are pointed slightly outward, with digit 2 parallel to the midline of the body. The footprints are also much closer to the midline here: this is likely because, unlike the short gait, the femur is rotated outwards – this is because the femur needs to rotate around the wide mass of the torso of the animal, which wasn’t a problem before in the shorter gait. Thus, as Day et al. suggest, this theropod was trading stability for speed. When you have a momentum going, it is much easier to maintain stability, of course. This long gait is displayed below:

“Long gait” biped walk, based on Ardley quarry tracks. Stride length is long, though perhaps this animal was not travelling full speed.

The longer stride as shown above, unlike the shorter gait, involves the hip “rolling” from side to side in a barrel motion. The torso would roll out of the way of the leading leg, providing space for it to come forward and impact the ground with force needed for speed.

So what’s the takeaway here? The Ardley quarry tracks (as well as many others) detail a “dual gait” in theropods (and probably other bipedal dinosaurs"). This involves a short gait, where the toes and femur are pointed inwards and the tibiae outwards, to maximise stability. The alternate, long gait, is employed when the biped is moving at faster, trading stability for speed - here, the toes point ever so slightly outward, along with the femur so that the leg moves around the bulk of the torso.

When you’re making art, models etc., make sure to account for this. In Neutral posture, the feet should probably resemble those in the “short gait” stance, with the toes pointed inwards to maximise stability.

To create the references above, I modelled the theropod Neovenator (why not) and posed the legs to match the footprints from the Ardley quarry tracks. These models matched the hypothesis of the original authors pretty clearly.

Thanks to Scott Hartman for providing a little more detail in to this locomotion.

Trackway images, and references: